In cities across the world there is a global crisis of housing affordability; the answer to this crisis may lie in a socially conscious approach to property investment.

In cities across the world there is a global crisis of housing affordability; the answer to this crisis may lie in a socially conscious approach to property investment.

June 2021

This article was originally published in Forbes on 25 May, 2021.

Introduction

What do you do as an investor if you can see that an asset class is attractive in terms of the hard numbers, but doesn’t work when it comes to the increasingly important, but softer, considerations of ESG – environmental, social and governance – investing? It feels like property is increasingly falling into this space. Ever-rising house prices have led to a situation where housing affordability has become a major political issue, a central conflict-ground in the inequality wars. Evidence of this isn’t hard to find. Firstly there was the report that almost 15% of homes sold in Hong Kong last year were ‘nano apartments’ – under 250 square feet.

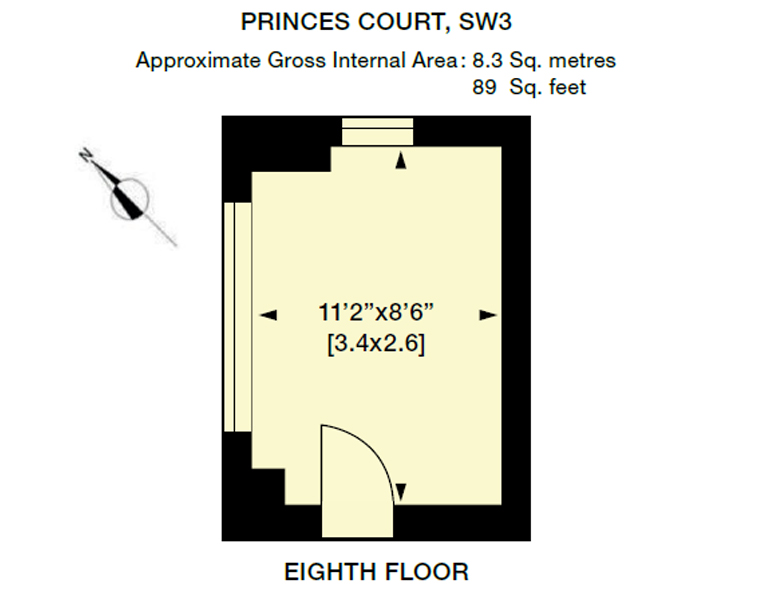

Then, as if to show that this is a global problem, there was the 89 square-foot ‘apartment’ for sale in Knightsbridge where, lying down, I think I’d have a good chance of touching all four walls at once (Figure 1). And here’s the really horrifying thing – at GBP150,000, I didn’t think it sounded over-priced (but then I’m almost immune to the horrors of London property).

Figure 1. 89 Square-Foot ‘Apartment’ for Sale

Source: Knight Frank.

A Housing Crisis

The world is facing a housing crisis that spans San Francisco, Cairo, Munich and Singapore, and, to a greater or lesser degree, almost every other major city you can think of. This crisis comes out of a complex combination of demographic shifts, the unintended consequences of central bank stimulus, political posturing and, perhaps more than anything, the – ugly word alert – ‘financialisation’ of property, such that the places we call home have also become an integral component of the global capital markets. The question is: what can we do to address this affordability crisis before it becomes a catastrophe?

Decent housing is one of the key pillars of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Functioning economies need functioning cities and yet in many of our major metropolitan centers, property is out of the reach of all but a small handful of the very wealthiest in society. In the world’s most expensive cities – Hong Kong, Vancouver, Sydney and London – median house prices range from 8x to more than 20x median household incomes (Figure 2). Given that mortgage loan-to-income ratios rarely stray north of 5x, and even then require hefty down payments, property has become a pipe dream for many on middle incomes.

Figure 2. The World’s Least Affordable Housing Markets

Source: Visual Capitalist, Demographia, Bloomberg.

Enter Community Housing

So far, so familiar. But I wanted to think about how an ESG-driven approach to investing in residential property might, along with the benefits it brings to the neighbourhoods it serves and the broader fight against climate change, help address the affordability crisis. My friend and colleague Shamez Alibhai developed the concept of community housing several years ago – he launched the first institutional social impact housing strategy in the UK in 2014 – but it is an idea that feels like it has gathered extra relevance at a time when responsible investment is gaining ever-greater momentum and when addressing the housing affordability crisis has risen towards the top of the global political agenda.

If, as F. Scott Fitzgerald said, the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function, then prepare to get your thinking caps on. The issue with housing affordability is one of cognitive dissonance – we find it hard as investors to equate the abstract idea of property investment with the very tangible notion of homes that people live in, that people fill with their own very personal hopes and dreams, homes that people love. The narrative in my hometown of London is one of nameless, faceless international buyers bidding up properties that they may never even visit, inflating housing out of the grasp of local communities and those providing essential services to them. Of property developers and housebuilders selling properties to the highest bidder from wherever in the world with no regard for the type of communities that will be left behind. Some on the left in the UK have called for tighter regulation of property as an asset class. What if there were another way, though, one that used the central place of property in our lives and societies as the starting point, rather than trying to pretend that a home was as abstracted as a stock or a bond?

Community housing is that other way. Recognising the power of the idea of communities and the value that decent housing adds to society, it’s an investment approach that takes a utopian vision – housing developments that are well-built, environmentally sustainable, well-connected and crucially comprised of a combination of different tenures – and making them a reality. It’s this mixing of tenures that is critical to the success of the community housing model. Modern cities have become – largely by dint of property prices – places that are segregated along socio-economic lines. Enclaves of decent, well-situated housing are bought up by the wealthy to live in and as investments to the exclusion of others. As previously affordable neighbourhoods are gentrified, lower-earners are driven ever-outwards into the far suburbs, or to other cities which are less far down the road of the affordability crisis.

Community housing looks to the past to build a better future. It was once the case that communities were made up of people from all different walks of life. Urbanisation and industrialisation created slums and gated developments in the 18th century (Sarah Blandy has written brilliantly on the way housing policy has shaped social policy in London) and while there have been admirable attempts to encourage mixed tenure developments, these have rarely been embraced by residents. If you step into some of the pricier areas of London, Munich, San Francisco and Sydney, you’re struck by how soulless they feel. These places lack life, they lack energy, they are places on a map, but they’re not neighbourhoods, they’re not communities. The exclusionary impact of house price inflation has destroyed the intangible but hugely valuable characteristics that make people want to live in a place, not just invest there.

Developments that offer a mixture of affordable and market-rate properties for people to purchase or rent immediately give character to a place. It’s an indictment of a city if the teachers in its schools, the nurses in its hospitals, the chefs in its restaurants all have to undertake long commutes in order to reach their place of work. Shamez often uses the image of a ladder when talking about housing affordability – the very lowest rungs of the ladder ought to be catered for by government agencies; what has happened with the inflation of property prices in many urban centers is that an enormous gap has opened up between these lowest rungs and the rung above them – effectively the space that the middle classes would once have occupied. Let’s imagine a couple of teachers each earning the average teacher’s salary of USD64,000 in San Jose, California. Median house prices in the city are a cool USD1.25 million. Our teachers would need to earn USD203,000 per year – or almost double their current wage – to afford a median-priced home. You can perform similar analysis for many major cities across the US and the world.

Community housing seeks to provide for precisely this demographic. Affordability is also a temporal idea, such that the properties that are made available to families should continue to be affordable for them in the future. For example, rent increases that far exceed wage growth maximise short-term returns but do not create stable communities.

There is an increasing weight of academic research showing the positive outcomes that accrue to all levels of the income scale in mixed tenure communities (there’s a particularly impressive piece by Raj Chetty here).

Conclusion

Developments combining affordable and market-rate homes offer a new vision of city life, one that continues to deliver impressive returns to property investors, but does so in a way that is sustainable and contributes to a more cohesive and democratic society. This is sustainable investing, not just because it seeks to preserve the environment, but because it is seeking to build long-term projects that deliver consistent returns over decades and even centuries. We think community housing is the future, not just for the UK, but for cities across the world. It’s an example of ESG investing at its most ambitious and radical, but it’s ideas like this that change the world.

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.