The story of the past 30 years has been one of the rich getting richer... Now inflation is coming to change that.

The story of the past 30 years has been one of the rich getting richer... Now inflation is coming to change that.

May 2021

Introduction

The markets tend to see inflation as bad news – it was rising inflation expectations that gave stocks the jitters in March. But what if we instead viewed higher prices as the cost of rebalancing a world that has been thrown out of kilter by decades of policy mis-steps and economic mismanagement? I wrote last month about the way in which inflationary pressure in the medium term is likely to be the price we’ll pay for addressing climate change, but inflation is deeply bound up with the other great 21st century crisis: income inequality.

Inflation and the ‘S’ in ESG

The manner in which large swathes of the world’s population have been left behind in the move to a technological and borderless global economy has driven social unrest and an increase in political extremism. Populist leaders have capitalised on this, standing on platforms that played into nostalgic visions of pre-globalised national self-sufficiency.

Of course, the protectionism and isolationist policies these politicians pursued were themselves inherently inflationary. Brexit, for instance, is already causing prices to rise in the UK, while Donald Trump’s trade tariffs (which President Joe Biden is expected to unwind) have caused a steep rise in the price of many goods. Now we have a series of major infrastructure investment packages whose aims are several-fold: to rebuild post-corona and address the climate crisis, certainly, but to do so in a fashion that helps to redress some of the deep inequalities that permeate contemporary life. So it is that Biden’s infrastructure spending plans are likely to prioritise the most deprived areas of the US Rust Belt, while Boris Johnson’s mandate in the UK is built on the promise of ‘levelling up’ deprived Northern communities.

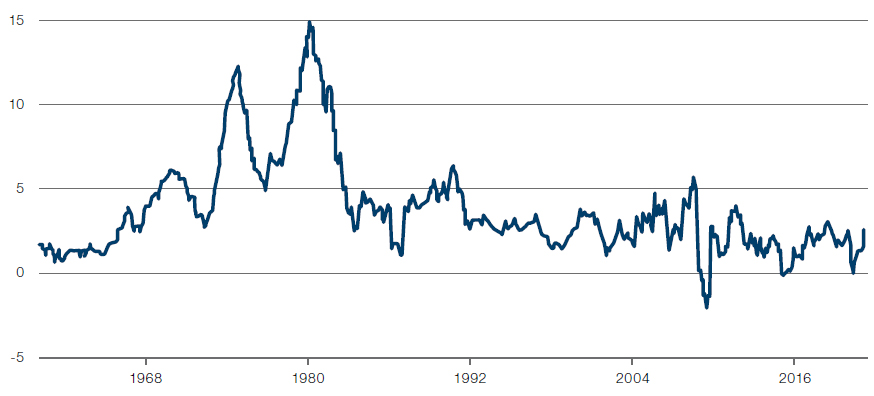

Social spending programs were at the heart of the last major spike in inflation. The period between the mid-1960s and early-1980s is often known as The Great Inflation and saw US CPI ratchet up from just over 1% in 1964 to peak at more than 14% in 1980. The causes were multiple, but a significant contributory factor was Lyndon B. Johnson’s ‘Great Society’ spending spree, which sought to eradicate poverty and redress racial inequalities.

Figure 1. US Inflation

Source: US bureau of Labor Statistics, Tradingeconomics.com; 1960 – 2021.

This debt-financed spending came at a time when America was already fiscally stretched as a result of the Vietnam War. Twinned with easy-money policies employed by the Federal Reserve in an attempt to counter unemployment, it led to a long and painful period of inflation that hammered stock and bond markets alike. More importantly, we saw that the rich were able to protect their wealth from the worst ravages of inflation by investing in commodities and other inflation-mitigating assets. It was the middle classes who were hit hardest, seeing cash savings wiped out and the cost of living rise sharply. The parallels between the 1960s and today are striking: governments seeking to spend their way out of several crises at once; a significant increase in the money supply; a loosening of fiscal controls and a Fed apparently committed to social justice.

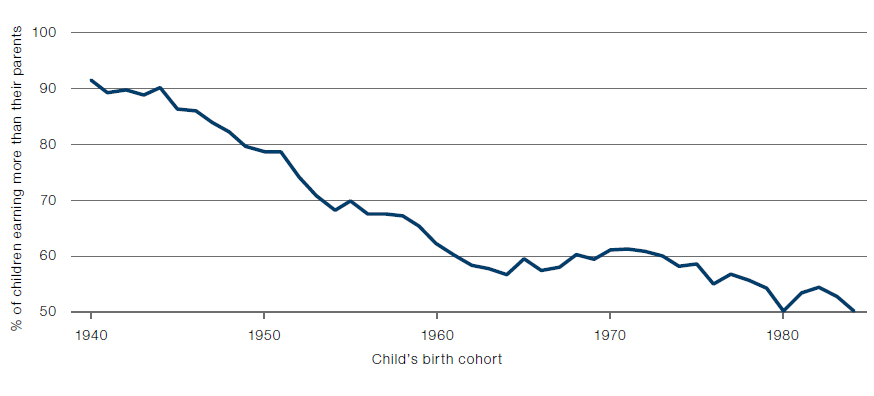

One of the major themes in the work of the economist Thomas Piketty is the idea that inequality is never economic, but always ideological. I remember a sign held by a protestor at a pro-Brexit march a few years back that said: “Not My GDP” – an elegant expression of the same concept. It’s a lesson that politicians would do well to heed – too many people have seen economic success stories playing out on television or in the press and recognised what an empty promise the trickle-down effect holds. Fewer and fewer young people are earning as much as their parents did, as Figure 2, from an excellent article by Raj Chetty, shows. Whether you call this the American Dream, or merely upward mobility, it is clear that something profound has happened to younger generations. The system is no longer working for them.

Figure 2. Fewer Young People Are Earning as Much as Their Parents

Source: Raj Chetty et al. 'The fading American dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940'; Sciencemag.org.

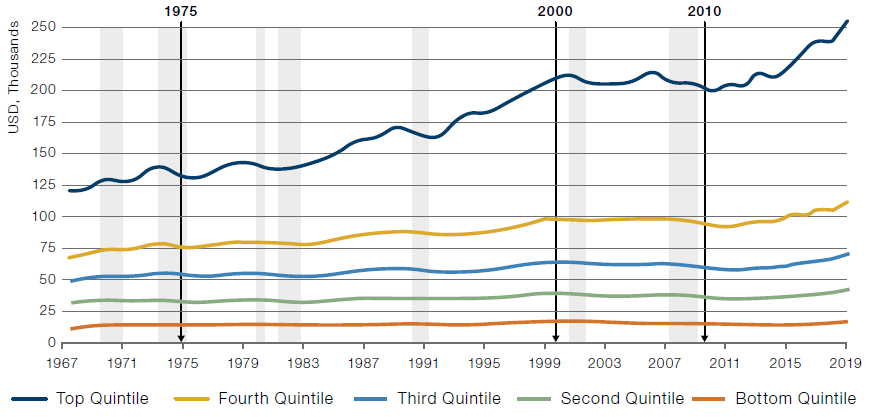

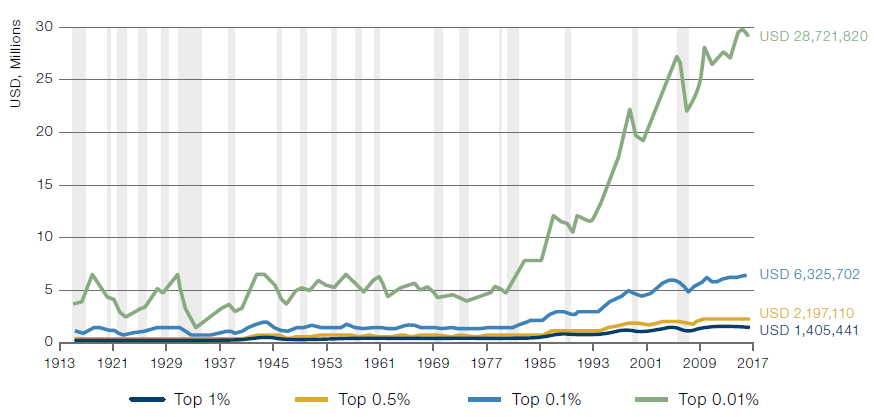

A look at Figures 3-4, from the Congressional Research Service, gives a clear idea of the extent to which the expansion of the past several decades has accrued almost exclusively to the very wealthiest in society. This is true both in broad terms – looking at income quintiles, where the poorest have seen their mean household income flatline in real terms over the past 50 years – and in the very highest echelons – where the 0.01% have been the clear winners of the latest iteration of global capitalism.

Figure 3. Mean Quintile Household Income

Source: Congressional Research Service based on data from US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements; 1967 - 2019.

Figure 4. Mean Income Per Adult, Select Percentiles (1913-2019)

Source: Income data from World Inequality Database, accessed 12 January 2021; Recession data from NBER.

The inflation that politicians are most keen to stimulate is one that has been profoundly – even chronically – depressed by the twin forces of technology and globalisation: broad-based wage growth. And here we come to the crux of the argument surrounding inflation and inequality.

Those firms that do not pay a fair wage are likely to be forced to pay one, with Joe Biden's plans to raise the US minimum wage from a miserly USD7.25 an hour (where it has stood for 12 years) to USD15. If companies are genuinely committed to addressing their ESG (environmental, social and governance) responsibilities, then one of the key aspects of the ‘S’ in ESG is paying decent wages. Just as investors are increasingly abandoning those firms who refuse to make or stand by climate pledges, there will be far greater scrutiny falling on those who fail to look after their staff, whether that be working conditions or wages. And just as the E in ESG – the environment – will stoke inflationary pressure, the S – social impact – has a distinct inflationary edge to it.

This is not the place for a discussion of Universal Basic Income, which seems to me hugely problematic at a practical level. Rather I’d like to make a more modest assertion: that, just as we needed to accept a degree of inflation as the cost of addressing climate change, recognising that not acting would lead to far greater issues, we need to welcome wage growth as a necessary corrective to several decades of underinvestment in the full spectrum of our communities. To allow continued stagnation would again invite a greater ill – further and more violent unrest.

Conclusion

There's a Bank of America index called the ‘Corporate Misery Indicator’ that tracks margin pressure on US firms, noting when wage growth outpaces CPI. It's a measure that has been notably benign for many years – you could even think of it as now being an ‘Employee Misery Indicator’. This needs to change. Investors should welcome a degree of margin compression – it's the sign of a firm that puts the sustainability of its business model above short-term profitability, that it values its employees and recognises the part that they play in its success. We've already seen companies like Amazon, Target and Kroger raising wages in an effort to get ahead of this issue. Those that don't will be left behind by investors and quality employees alike as we move into the new inflationary regime.

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.