What might investors miss if they stick to the common ways of deciding their strategic FX hedge ratio? We ask if ignoring profit and loss dynamics puts your portfolio in peril.

What might investors miss if they stick to the common ways of deciding their strategic FX hedge ratio? We ask if ignoring profit and loss dynamics puts your portfolio in peril.

5 June 2024

For multi-asset investors, ‘higher for longer’ interest rates have upset the ‘normal’ conditions governing a range of risk/return levers in their portfolio, from inverted yield curves to rising correlations. Another key consideration is how currency markets affect portfolio returns.

Foreign exchange (FX) markets have seen their share of tumult recently. Previously reliable approaches, such as the ‘positive carry’ trade on the AUD/USD currency pair, have reversed. In this light, it’s not surprising that one of the most common questions we get from clients is how to manage their currency exposures.

Below, we examine if typical approaches to hedging FX hold up across different market regimes – and other factors investors may wish to consider.

How to hedge

Historically, there has been a wide range of ways investors have conceived of strategically hedging their FX risk. These range from none at all, to the idea that portfolios should be fully hedged.

Modern portfolio theory has evolved to become the market standard, and Minimum Variance, or 1+β, is a common shorthand for multi-asset portfolio investors. This approach suggests that the optimal hedge ratio is one that minimises portfolio variance. Put simply, it is:

1+ the beta of foreign assets’ excess returns to FX forward returns

In this context, the ‘beta’ means the sensitivity of the client’s portfolio moves to foreign currency prices, and therefore investors may choose to take currency risk when it is negatively correlated: a portfolio diversifier.

In principle, the logic of employing modern portfolio theory is hard to fault. It aligns well with how investors typically approach other assets in a strategic asset allocation framework. But when applied to strategic FX hedging, many conceive of it as a ‘free lunch’, because they assume hedging can often be done at a minimal cost and that FX forwards are good predictors of future FX spot returns.

In practice, estimating FX risk is far from straightforward, as FX returns are not well predicted by FX forwards at various time horizons (Figure 1). Additionally, the cost of hedging does not remain static through different points of the market cycle. It can have an immediate, material impact on portfolio returns.

Figure 1 – Missing the mark: The ‘forward’ rate can be a weak predictor of future currency values

Source: Man Group, Bloomberg.

Theory meets practice

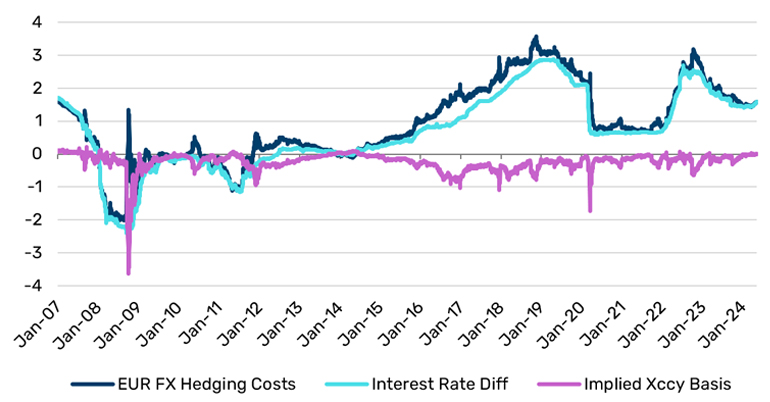

As mentioned earlier, the 1+β approach has various assumptions embedded within it, which may not hold true in practice. Ignoring material hedging costs (or profits) is an obvious one to call upon. Interest rates have provided a reasonable yardstick for the total hedging cost in many market regimes. As Figure 2 shows, since 2007, EUR/USD hedging costs have moved in line with the interest-rate differential for much of – but not all – the time.

Figure 2 – Under pressure: Hedging costs may jump during times of market stress

Source: Man Group, Bloomberg.

However, during times of market stress, costs which may appear predictable when markets are buoyant can grow significantly during a squeeze. For example, currency hedging requires derivatives to be bought and sold. During periods of market turbulence, demand for safe-haven currencies may grow while liquidity dries up, suddenly pushing up the cost of these instruments. The navy line in Figure 2 shows how hedging costs spiked during the global financial crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic, driven by higher premiums demanded for hedging instruments (i.e. implied cross-currency basis).*

In addition, there are fixed costs to consider. The operational or management costs of running an FX hedging program may not be meaningful on an individual basis, but when they are excluded entirely from cost calculations, they have a cumulative effect.

Conclusion: Theoretical niceties ignore fundamental practicalities

1+β is a common way that investors conceive of strategic currency risk. However, we think that this approach may ignore important elements when deciding the FX hedge ratio for a multi-asset portfolio, particularly given the current shift in market regime. In particular, the cost or profit of hedging is dynamic, and may be at times a significant driver of portfolio returns that an investor should not ignore. In this light, we think investors should try to conduct a more comprehensive and frequently reviewed assessment of all risks, returns and costs trade-offs.

*shown as a negative figure per market convention.

With a contribution from Pedro Castro, Head of Portfolio Engineering, at Man Group.

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.