Governments make crucial decisions regarding sustainability and bonds are a key instrument for financing their multi-year plans and operations.

Governments make crucial decisions regarding sustainability and bonds are a key instrument for financing their multi-year plans and operations.

November 2023

Introduction

In our ‘Path Less Travelled’ series on multi-asset sustainable investing, we delve into less-explored asset classes. Our first paper addressed the underappreciated potential of commodities in responsible investing. Now, we turn to government bonds. Governments play a significant role in sustainability, and bonds, as key financing tools, are crucial to any responsible investment (RI) framework. This paper addresses the role of government bonds* in portfolios, the disparities between emerging and developed markets and the potential influence of investor action.

The role of government bonds in an investment portfolio

Before discussing ESG integration, let us first remind ourselves why investors may hold government bonds:

Owing to these characteristics, government bonds typically make up a meaningful weight in investor portfolios.

1. Stability of returns and income: Developed market government bonds are generally considered low-risk investments and offer a relatively stable income stream.

2. Diversification: Including government bonds in an investment portfolio can help diversify risk due to their historical low correlation to equities.

3. Liquidity: Government bonds are often highly liquid. This provides investors with flexibility to rebalance portfolios or access cash when needed.

4. Capital preservation: Developed market government bonds may help protect the value of a portfolio during times of market stress.

5. Return enhancement: Emerging market government bonds may offer higher expected returns to compensate for their higher risk when compared with those issued by developed governments. However, these bonds may deliver less stable returns and may not be as effective at preserving capital.

Owing to these characteristics, government bonds typically make up a meaningful weight in investor portfolios. Bonds are the ‘40’ in the ubiquitous 60/40 portfolio, and government bonds make up more than half of the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index. In a balanced multi-asset allocation, such as risk parity, they are likely to represent an even higher weight.

While investors can engage with companies and apply pressure for them to improve, governments can legislate to force and enforce improvement.

Why consider responsible investing in government bonds?

Governments set the rules for investors with regards to environmental and social laws and regulations. While investors can engage with companies and apply pressure for them to improve, governments can legislate to force and enforce improvement. A government’s role is to govern, so they are likely to be most associated with governance. However, they also play a key role in many of society’s challenges such as lowering carbon emissions and reducing poverty.

Notably, some countries are more aligned with tackling these challenges. For example, we can look at environmental policy, climate action and the relevant laws governing workers’ rights to form a view. Figure 1 shows the CO2 emissions per capita in metric tons for three high income countries, with the US producing roughly triple the emissions per head as the UK, and over four times that of Sweden.

Figure 1. CO2 emissions per capita in three high income countries

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: The World Bank Sovereign Data Portal. Data as at 31 December 2019.

This is just one metric among many, but it shows how data can be used to form views on sovereign investments. As we later discuss, pressure can be applied by shunning (or even shorting) those countries which are doing the most damage while championing those that are improving and are most aligned with RI preferences.

Different countries are at varying stages of economic development, which inevitably shapes their capacity to implement ESG policies.

Should we differentiate between developed and emerging markets?

We acknowledge that different countries are at varying stages of economic development, which inevitably shapes their capacity to implement ESG policies.

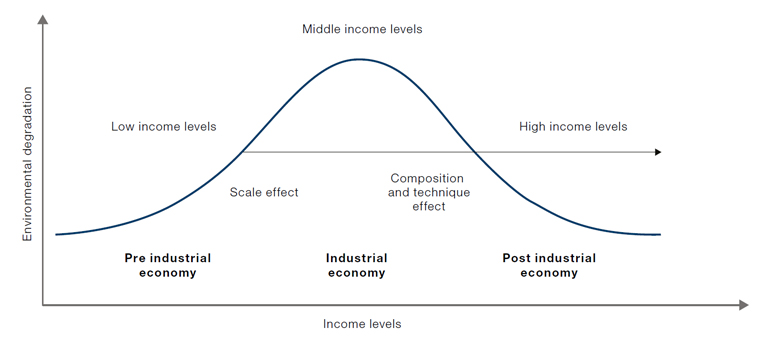

The environmental Kuznets curve discussed by Sarkodie and Strezov1 proposes an inverted U-shaped relationship between environmental degradation and economic development. In the early stages of development, environmental degradation increases as a country industrialises. However, after a certain level of income is reached, the trend reverses, and societies start investing more in the environment, leading to a decrease in degradation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Environmental Kuznets curve

Source: Sarkodie and Strezov, 2018.

For investors forming views on a government’s RI credentials, this likely means using different frameworks for developed and emerging nations to account for economic development and other differences.

These effects mean some form of redistribution is likely required to help lower income countries reduce emissions. This could be via financial assistance or the transfer of technology from developed to developing nations, for example. Developed nations pledged to mobilise $100 billion for this purpose in 2009. However, this goal has yet to be met.2

Beyond environmental concerns, developing nations may face more basic social and governance challenges, such as ensuring access to clean water, basic human rights and government corruption. Their ratings might therefore reflect different priorities to higher income countries.

For investors forming views on a government’s RI credentials, this likely means using different frameworks for developed and emerging nations to account for economic development and other differences. Otherwise, we expect most portfolios would end up investing in developed markets only, with limited scope for influencing ESG outcomes in emerging markets. Hartzmark and Shue suggest that incentivising the biggest corporate polluters to cut emissions is key to meeting long term low carbon goals.3 Applying this thinking to governments, investors need to engage with both developed and emerging nations, particularly countries that are, or have the potential to be, large emitters.

How can investors influence governments?

In order to lower emissions or promote better social practices, investors need some form of influence. With respect to governments, this could come in many forms, including:

1. Altering the cost of capital: By buying (or selling) the country’s debt, downward (or upward) pressure is put on yields, altering the cost of capital and incentivising countries to improve their ESG performance. For governments committed to improving climate policy or their record on human rights, for example, demand for their debt will be higher, lowering the cost of borrowing. The opposite is true for poor performers.

Governments, like companies, care how others perceive them.

2. Perception and sentiment: Governments, like companies, care how others perceive them. Lavish spending on hosting the Olympic Games to assert prestige is just one manifestation of this. By endorsing countries which are more RI aligned and shunning those that are less aligned, market participants can influence governments, which may want to be perceived as leaders on the environment or on human rights. Governments care about this, with a good example being the World Bank’s ‘Doing Business’ report, which was discontinued in 2021 following allegations that some countries had been manipulating data to increase their scores and thereby improve their external image.4

3. Engagement: Investors can join forces with other stakeholders to engage with governments on issues such as climate change. This can involve expressing concerns, providing feedback, or advocating for specific policy changes. An example is the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) which incorporates over 400 institutions managing $65 trillion in assets and which, in 2022, sent a statement urging governments to increase their climate policy ambitions.5 Engaging and building public pressure in this way is an avenue for influencing policy.

4. Sustainability/green bonds: Investors can buy green, social or sustainability bonds issued by governments, which are intended to finance projects with positive environmental or social outcomes. Investing in sustainable bonds sends a signal to the government, primarily having influence via the perception and cost of capital channels described above.

Treating investment in bonds and bond derviatives as equivalent may help reduce greenwashing risk.

Investors may access government debt via bonds or bond derivatives. While buying or selling derivatives doesn’t provide direct funding to the government, it influences perceptions of a government’s credit risk and can impact borrowing costs, providing a channel of influence for investors, as they send a signal of endorsement or disapproval to a country’s behaviour. In addition, it is important to disincentivise bad actors who may look to substitute bonds with derivative investments to greenwash their portfolio if the RI reporting requirements on derivatives are less stringent. We acknowledge that for some investments, such as sustainability or green bonds, buying the bonds themselves (rather than derivatives) may be the only option. However, derivatives are available on many regular bonds. It therefore seems sensible to treat bonds and derivatives investments in government bonds in the same way with regards to RI.

What data can be used?

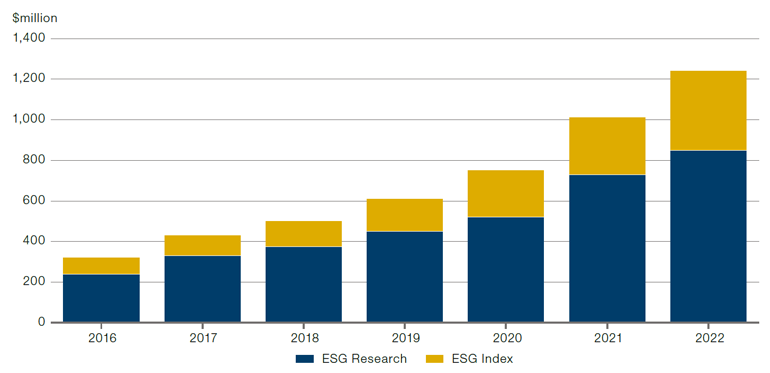

Figure 3 illustrates the growth in the value of ESG data from 2016 to 2022 using provider accounts to estimate the size.

Figure 3. Market size for ESG data

Source: Opimas to 31 December 2022.

Growth has been driven by data for research purposes, but there is also demand for RI indices for benchmarking and reporting.

There is now a wealth of data available, not just for corporations but also for governments, which can assist investors in assessing the RI credentials of their investments. Growth has been driven by data for research purposes, but there is also demand for RI indices for benchmarking and reporting, as shown in gold in Figure 3. Indices such as the FTSE ESG World Government Bond Index (WGBI) incorporate a scoring system to over- or underweight good or poor ESG performers, respectively, helping investors to benchmark their portfolios.

In terms of the data available, investors can form RI views using primary sources, such as the World Bank, the United Nations or government-related institutes such as the UK’s Office for National Statistics. Alternatively, specialist providers such as MSCI and Sustainalytics combine the primary data to deliver off-the-shelf scores, which could be considered holistic views on the ESG performance of a country. Some of the metrics that can be considered for an environmental score include:

- Greenhouse gas emissions per head

- Renewable energy percentage of total energy consumption

- Air pollutant concentrations

- Water efficiency

To ensure no single source dominates the view on ESG, multiple sources can be combined and supplemented with primary data.

For investors, maintaining a catalogue of data from primary sources is laborious, so selecting data points that are particularly relevant to their portfolio is important. If using provider scores, these should be investigated to ensure their methodologies align with RI beliefs. If we look specifically at MSCI scores, the E, S and G can be investigated individually. For example, if a goal is to allocate to governments who are managing their environmental resources effectively, the MSCI ‘E management score’ incorporates metrics such as energy management, resource conservation, and water management.

Much has been written about the challenges that surround ESG data.6 To ensure no single source dominates the view on ESG, multiple sources can be combined and supplemented with primary data sources that the investor believes are particularly relevant to their government holdings.

Improving RI outcomes versus protecting portfolios from RI risk

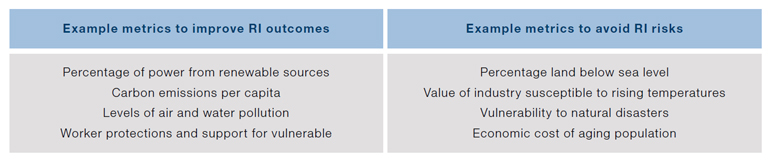

Everything discussed so far relates to investors aiming to improve RI outcomes, such as better climate policy or labour laws in a country. This should not be confused with minimising RI risk, which is focused on avoiding damage to the returns of an investment portfolio due to RI factors. Many investors conflate these separate concepts.

An investor may divest to protect their portfolio, but this action is not the same as improving the climate or driving positive change.

Improving RI outcomes means supporting governments which are aligned with investor RI beliefs. For example, the Netherlands tends to score well on social measures, such as worker protections, including termination rights, working hours and leave entitlements. An investor may therefore support investment in the Netherlands on this basis. This is different to trying to protect a portfolio from RI risk, such as climate change. Staying with the example of the Netherlands, the prevalence of low-lying land, and therefore high susceptibility to climate change, means a high climate risk for this country. An investor may divest to protect their portfolio, but this action is not the same as improving the climate or driving positive change in other areas. Figure 4 illustrates some differences between improving RI outcomes and reducing RI risk.

Figure 4. Targeting improved RI outcomes versus reducing RI risk

Source: Man Group database.

In our view, investors should therefore be clear on whether their goal is to improve RI outcomes or to protect portfolios from RI risk, and they should avoid conflating these concepts when selecting which governments to invest in.

How does government RI data impact investment portfolios?

Incorporating RI information into an investor’s sovereign portfolio by upweighting top performers and down weighting or removing the worst performers will change the allocations and therefore the properties of the portfolio. Investigating this in full is beyond the scope of this paper, but we believe it will impact characteristics such as:

1. Geographical composition: In developed markets, Nordic countries typically score well across environmental and social measures. A portfolio of government bonds may therefore have higher weights in countries such as Sweden and Norway, and lower weights to the usual sovereigns that dominate government portfolios, such as the US and Japan.

2. Credit rating and yield-to-maturity: Developed market government portfolios tend to be of high credit quality and offer relatively low yields. Tilts based on RI data are therefore expected to have a small impact on these metrics. Incorporating emerging markets could boost portfolio yield, but at the cost of reduced portfolio average credit rating.

3. ESG score: We expect that tilting a portfolio of government bonds using ESG data will provide a boost to the overall portfolio ESG score. This is true with respect to the ESG metric that is used to do the tilting (obviously) but due to disagreements across providers, it may not necessarily hold true across all ESG metrics. For example, using environmental scores provided by MSCI to tilt the portfolio will boost the MSCI environmental score, but may have unintended impacts on other measures, such as portfolio emissions. Investors therefore need to be clear which providers are most aligned with their RI values, or may want to combine scores.

Investors need to be clear which providers are most aligned with their RI values, or may want to combine scores.

4. Performance: Developed market government bonds tend to be low risk investments with similar macro return drivers, so the incorporation of tilts based on ESG data is likely to have a small impact on long term performance.

5. Volatility and correlation: For the same reasons as above, tilts are expected to have a limited impact on portfolio risk measures such as volatility and correlation.

Figure 5 compares the long term returns of two government bond portfolios, both based on the ICE BofA Global Government Index (GGI) with one also incorporating RI based exclusions.

Figure 5. Comparing government bond returns

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Man Group, MSCI, Sustainalytics, ICE BofA indices. GGI and GGI RI have been constructed by equally weighting the underlying constituents by their risk contribution to total portfolio risk. GGI contains all constituents. GGI RI contains all constituents deemed ‘environmentally aligned’ by Man Group’s internal Sustainable Investment Framework, which combines data points from multiple providers to form a view. For reference, the GGI RI contains: Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, Austria, Denmark, Finland, UK, Germany, France, Ireland and New Zealand.

The dark blue line contains all the countries in the GGI. The gold line contains only countries in the GGI RI deemed to meet environmental criteria set out by Man Group, including metrics on renewable power and emissions, for example. As shown, the lines track closely, with some outperformance seen from the regular index after 2016 when the GGI benefitted from allocation to peripheral European countries such as Italy and Spain. The spread to German bunds came down steadily in a number of these countries over several years after the European Central Bank began its public sector purchase programme in December 2016. As these countries were excluded above in the GGI RI, the portfolio did not benefit from the uplift. However, over the long run, performance is similar.

This simple example suggests it is possible to incorporate some RI considerations, while still maintaining the attractive properties offered by government bonds in the context of an investment portfolio.

Governments play a pivotal role in addressing environmental, social, and governance challenges and bonds are vital to finance their actions.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have explored the usefulness of government bonds in an investment portfolio, the reasons why RI should be considered in such investments, and how investors can exert influence on governments. We have also discussed the difference between developed and emerging markets, the data required for RI considerations, and the impact on investment portfolios

Clearly, government bonds present an opportunity for investors to contribute positively to RI outcomes. Governments play a pivotal role in addressing environmental, social, and governance challenges and bonds are vital to finance their actions. By adjusting portfolios to favour countries that align with their RI beliefs, investors may be able to stimulate policy changes and social transformations, while still benefitting from the desirable portfolio characteristics delivered by bonds, namely diversification, liquidity and a stable return stream.

* Throughout, we use ‘government’ and ‘sovereign’ interchangeably.

References

1. S. A. Sarkodie and V. Strezov, “Empirical study of the Environmental Kuznets curve and Environmental Sustainability curve hypothesis for Australia, China, Ghana and USA”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 201, 2018, Pages 98-110.

2. OECD, “Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal”, https://www.oecd.org/climate-change/finance-usd-100-billion-goal/

3. S. M. Hartzmark and K. Shue, “Counterproductive Sustainable Investing: The Impact Elasticity of Brown and Green Firms”, SSRN, 2022.

4. The World Bank, “World Bank Group to Discontinue Doing Business Report”, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/statement/2021/09/16/world-bank-group-to-discontinue-doing-business-report

5. IIGCC https://www.iigcc.org/ media-centre/more-than-500-institutional-investors-from-around-the-world-join-forces-to-urge-governments-to-step-up-climate-policy-ambition

6. B. Jonsdottir, T. Sigurjonsson, L. Johannsdottir and S. Wendt “Barriers to Using ESG Data for Investment Decisions”, Sustainability, Volume 14, 2022.

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.